I am a field, discouraged of forest.

Always—a conversation between humus and seed, light-struck.

The timber line my spine, the crickets my voices.

Always—a scented trail, a wayfinding, turning head.

Always—cloud-grazed then abandoned to the world.

The soft-bodied are safe on the grasses of me.

The grasses of me are safe on the hills of me.

The hills of me are safe in the valley of me.

The valley of me is bridged and dredged,

but look at that loam.

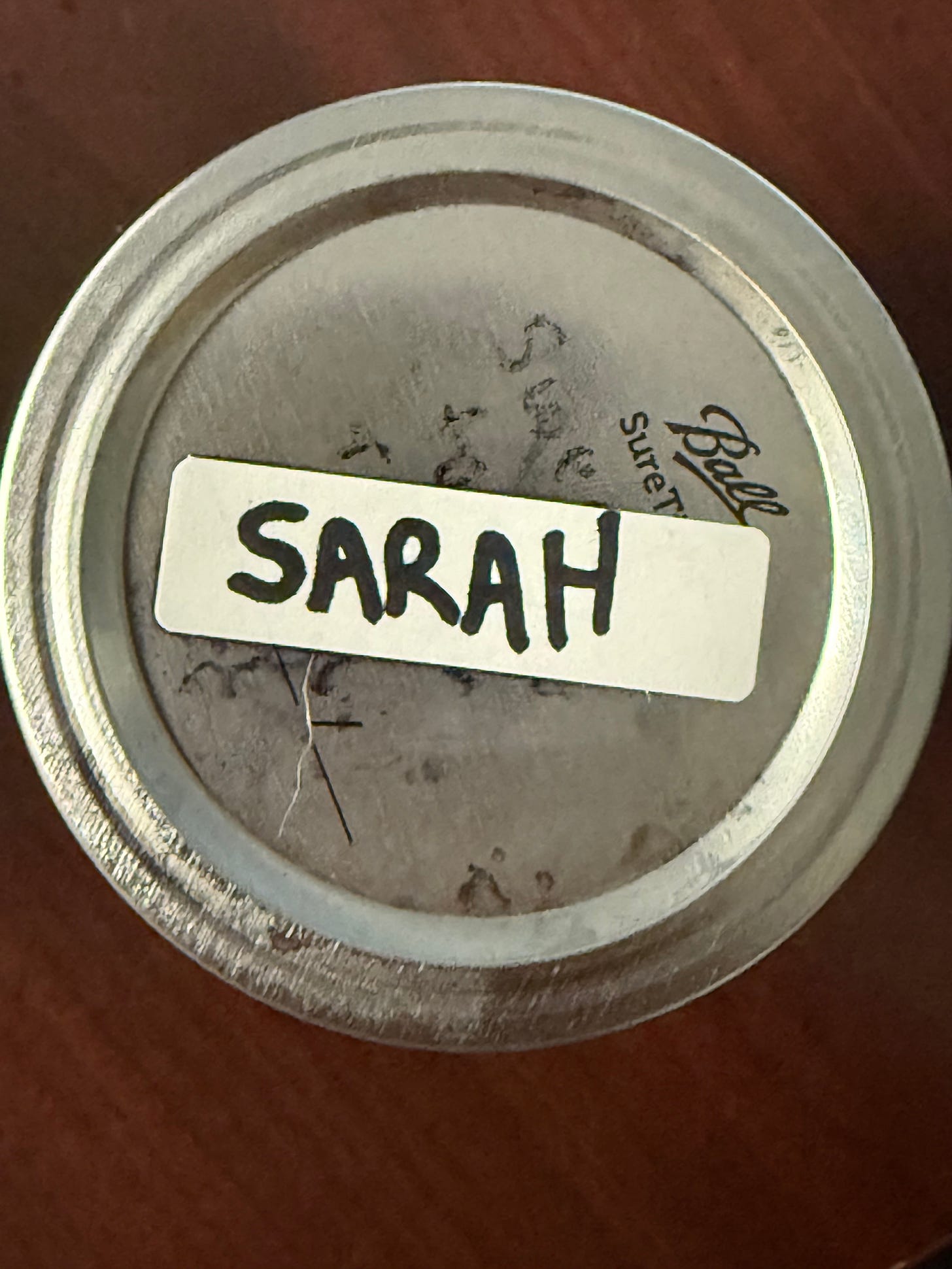

At work, I wrote SARAH on a label on my mason jar of coffee creamer. First, I was stunned by the neatness of the letters. Next, I was intrigued by the word on the label. Its phonemes: both exhalations, one a hiss and the other a roar. Yet together, they are a flat field of long meadow grass, blowing in a breeze. I have been to the exact field it conjures. It is a memory that I do not want to fully remember, wanting to keep the mystery. The landscape of Sarah has a dirt road running through it. Some of the dirt is dust suspended in the air as if a pick-up truck recently passed but the truck is nowhere to be seen. A house is in the distance. Hills are in the farther distance. There are chicks roaming around somewhere, but they can’t be seen. The sun is setting and everything is illuminated in an hour of gilded light. Despite the beauty of clouds, the sky is cloudless and beautiful. In this field, I am a child unmonitored and ageless. I am alone. And you, adult reading this, are having a beer with the other adults in that house in the distance, the windows aglow. You’re not worried about me and unapologetically, I don’t care about you.

*

I just dissociated from my name, I told my colleague after I put my creamer in the refrigerator. I told him about how this sometimes happens. I see the-word-that-is-my-name or hear it come out of someone’s mouth and it’s suddenly beautiful, mysterious. Oh, and it belongs to me, which is even stranger, because I am not the type of beautiful that comes to mind with that word. In my mind, people named Sarah are always magical. People named Sarah intrigued the romance out of boy-next-door John Cusack characters. People named Sarah were muses with mermaid hair. They’re whimsical, but not nauseatingly so.

In a rural landscape in the deep Baptist south, the writer Flannery O’Connor conjured a lumbering, hulking character named Hulga Hopewell. She hobbles and limps along the dusty road. The flat fields are punctuated with farm animals and barns. The sky is lucidly bright and the Good Country People, seemingly not so. For every God-fearing remark from her mother is a nihilist atheism broiling in Hulga’s mind. A childhood hunting accident led to her wooden leg which she dragged along with her philosophies and faithlessness, gracelessly. She felt ugly, thus changing her legal name from Joy to the hefty Hulga.

I also lumber and hulk around, Sarahlessly. Like Hulga, an injury rendered me Joyless in my movements. Nothing about Hulga and me sends the dust flying because being slower than dust renders one a studier of dust.

Hulga heaving herself up the steps. Hulga listening to god-praise through the walls. Hulga rubbing her wooden leg shiny-smooth as she reckons with the heart issues that led her from university back home again. How the wooden leg glistens, beautiful thing. How strong it is supporting the weight of her southern discomfort.

Throughout childhood, I was unable to say my own name. Silla? strangers would ask me, misunderstanding my impeded speech. Cecilia? I dreaded being asked my own name. As a typical child staying up late at night, I turned the channel to Cinemax—or Skinemax as they say—where Cinderella turns into Skinderella at midnight. I came across an erotic TV show called “Emanuelle in Space”. I had never heard of the name Emanuelle and immediately adored how it sounded and felt. Like satin. Like a velvety flower blooming. I was able to say it and it felt more like reciting a line of poetry. An avid collector of words and sounds (lists and lists of them), Emanuelle topped my name list, evoking in me the same feelings as the words ennui, lament, and levee. Es, Ls, and Vs were soft, fluid landscapes that yielded to my every movement. Long wavy lines, like delicate spider silk. I wanted to be an Emanuelle, but I was not the right landscape for such a word. Short, shy, and unpretty, I could be more likened to Clunk or Froth, like a charming hobbit.

I can say the word Sarah now. The transition happened as if cellular, as if all the cells of my adolescence had been replaced by more pronounced, sharp-edged cells that can growl and roar Sarah. In fact, a colleague once told me that my Rs are “crispy”. Regardless, I am still removed from the landscape of Sarah. I am less a field of tall grass during the golden hour and more a Sally, which strangely enough is the nickname for Sarah. Sally is a bird shaking their wings dry. Sally is a landscape of powerlines upon which those birds are perched. Sally is a child’s wading pool of hose water glittering in the sun. Sally is the smell of hose water. Sally is a babbling brook littered with beer bottles. Sally is always out in the rain. Sally observes from above or from the outside. Sally is the melted roadside pavement tar that nocturnal animals lick from their feet under the moon’s vigil.

*

To be named is to be vulnerable. To be named is to be a conjurer of memories and associations. It is not uncommon to meet people and their name just doesn’t sit right. You meet a Heather and they’re not a garden of flowers or an Appalachian plateau. You meet a Kimberly and they are not a crow with something shiny in their beak. You meet a Chad and he’s not an empty parking lot full of puddles that reflect just him. You meet a Brad and he’s not a closet of baseball caps, rarely seeing light. In our age of careful curations of self—be it online or in “real life”—people have “dead names” sometimes carefully or not carefully choosing a new name or identity that reflects their selfscape. And we’re fluid, aren’t we, always changing, always defending and reckoning with selfhood. Always needing to know what we are. Always needing to be perceived how we desire. Protecting our egos. We are but taut strings being plucked into vibration and those vibrations change. And the songs of ourselves are plucked by absolutely everything.

*

I don’t like anything. I texted this to my husband Brian who was in another section of the department store where I was shopping for a dress for an upcoming wedding. I know more about how to be a landscape than how to be a body. Come, friend. Hang a hammock upon me and enjoy my sky. By the way, what book do you have there? Dig a hole in me and plant a tree, bury your burned letters, explore the entangled roots in my dark humus. Toss a line in the stream of me and listen to the catbirds until your line is taut with a good catch. But put a dress on me? Empty a bag of makeup in front of me? The most I will do is check out the lipstick. Take me to a wedding and I care less about the outfit I’m wearing and more about the escape routes where I can have quiet moments with people. Take me to a beach and I care less about the swimsuit and more about the late-night walks in that liminal space between land and sea. I wish I was a normal woman who wants to be pretty, I have said recently to friends, knowing that I’ll have to attempt to look nice for the wedding soon. I put an outfit on and I feel it too much on my skin and have to take it off. I don’t know how to dress for my wonky “body type” and have no desire to learn. I don’t care about fashion. I knowingly wear clothes that are ill-fitting and I can’t seem to really care. When I had poison ivy rashes on over 60% of my body—including my face—I simply wore it like how a branch wears a coat of lichen. Because this flesh I’m in is a body and things simply happen to bodies. This body has expanded and retracted. It has broken in certain ways. It has changed color and texture. When I wonder if I’ve dissociated from having a body, I instead realize that it’s quite the opposite. I’ve reckoned with it in the way that Ram Dass suggested we reckon with other humans.

A bible salesman named Manley Pointer knocks on Hulga’s door one day. From another room, she listens as he charms her mother whilst praising the lord. Despite Hulga’s cynicism regarding his faith, he is intrigued and asks Hulga out on a date. Eager to share how her intelligence compensates for her lack of grace and beauty, she agrees. She calls his bluff when she agrees to climb a ladder up a barn loft where they can be alone, the pastures and endless fields sprawling below them. Just because she has a wooden leg doesn’t mean she can’t climb a ladder. She comes around, though, to this charming Manley Pointer. So much so, in fact, that when he asks to hold her leg, she obliges because hey, maybe he is good country people. Much like how a woman may vulnerably lift her skirt for a man, she removes her leg and hands it to him. He proceeds to put it aside, the first slight that strikes Hulga and the reader like the alleged bullet that took her leg as a child. He opens a bible and Hulga sees that it is hollow and full of pornographic images, a whisky flask, and condoms. Her demands for her leg go unmet. The last thing Manley Pointer says to Hulga is you ain’t so smart. I been believing in nothing since I was born. He takes her leg and climbs the ladder down the loft, abandoning her. She watches his slim figure disappear into the pastoral landscape.

There are feathers on my ankles. Or maybe they’re centipedes. Or ferns. A long line of white skin glistens on each side of my ankles and from them splays vanes or legs or thin segments. A steady-handed man named Gary once opened my skin with a scalpel and saw the brokenness in me. He saw parts of me that I will never get to see. He does this for a living, using blades and clamps. But he took nothing away and instead, like a crow he gifted me shiny things. 16 screws, 2 pins, and 2 plates later, he tied me up with string. Over time, like the ghostly trails left on the land by a meandering river, my feathery scars appeared, glistening, tender, and flightless. Told that I’d never walk comfortably on uneven terrain again, I laughed under the hospital’s fluorescent lights, tubes like vines sprouting from my arms and urethra.

Abraham’s wife and mother of Isaac, the barren but hospitable Sarah laughed at God. God’s message that she would bear a child at her ripe, old age had her doubtful, laughing to herself the way a woman may laugh to herself if told that men understand any aspect of being a woman. Sarah—an infertile, brown landscape under what I imagine is a bright blue sky—is blessed with tumbleweed potential. Tumbleweeds, dead and uprooted, are teeming with seeds and highly flammable. Get enough tumbleweeds together under certain conditions and a fire will ignite. I imagine fire tumbling across the wind-blown landscape of Sarah. The seeds, flying and popping and singed, spread across the scratchy, pubic landscape. And as we all know very well, it takes just one seed to create change of a biblical proportion.

*

The reader doesn’t learn what happens to Hulga. She sits there, one-legged and vulnerable, in the lofts of our imaginations. The 40-billion-dollar self-help industry suckles at our vulnerabilities. Days ago, the small village we live in experienced a deluge of rain—1.7” of rain in a half hour. The rain subsided before I came home from work; however, I made it home just minutes before the local roads were impassable due to flash flooding. The riverside road I had driven on just five minutes ago teemed with a quick current of frothy, brown water. Tributary streams were no longer babbling veins amongst the skunk cabbage and meadow buttercup. Instead, they were shapeless, moving beings spreading onto any surface that gravity allowed. Dry roadside ditches were rendered intrepid streams of black, rapid water. I marveled not only at how water follows a gravitational course but at the design of roads: how deep a ditch should be, where the sewer grates should be placed, how the road should curve to prevent a, b, and c. I marveled at the lack of design, as well, as I watched water go off course on a simpler route, down into the unsuspecting woods.

But it’s not exactly the flood that I want to talk about here. I want to talk about vulnerability. Because later in the evening, the birds carried on at the feeder. The next day during our riverside walk on the once-flooded road, we admired the waterlogged skunk cabbage glowing bright green in the drainage ditches. The river itself appeared vivacious. Other roadside flora, while water-swept, raised their tendrils to the sky in a seemingly mechanical sun-praising way. Yes, flooding leads to displacement, a changed landscape, and can disrupt ecosystems. But while walking along that road, I couldn’t help but wonder if the flooded soil had been enriched with new nutrients. Maybe, like the burning tumbleweeds, some kind of life had been planted. The day after that, I walked the same road again in the rain. For the first time ever, I noticed small snails that looked like large seeds all over the road.

Humbled Hulga still sits in the loft of my imagination. When I hobble around or walk on uneven terrain, I think of the landscape changing before her very eyes, day-in, day-out, as she sits with her new-yet-again body. Did her interaction with Manley Pointer point her mind into a different trajectory? I imagine her looking at the loft floor and finding stories in the wood grain. I imagine her rubbing that wood into soft shininess. I imagine that when she lays her head down at night, she faces the world as it fades into darkness and back into light. I wonder if she will change her name yet again. Hulga. Hul-ga. Whole-god-damned-world.

The tall meadow grasses of Sarah host an orchestra of insect and bird song. The dust in the air has settled and if you look closely, the blades of meadow grass are graced with it. The house in the distance is still full of people but it is always unlocked. The trees in the ecotone provide shade for reading a good book or thinking about what to write or talk about next. If I walk far enough into the field, there is a me-shaped space in the flattened grass. It fits me just right even when I roll over or spread out. Some grass is pulled out by the root. There is something satisfying about pulling blades of grass from the ground, one at a time. I sit in the Sarah-shaped space and clench a grass blade between two fingers and gently pull until its white base slips from the dirt’s grasp. Knowing that the white base is cool to the touch, I run it along my lips.

![And so I practice turning people into trees." - Ram Dass [640x960] : r/QuotesPorn And so I practice turning people into trees." - Ram Dass [640x960] : r/QuotesPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!hJo3!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F56fb182f-d35f-4208-8474-4009d76c24a3_640x960.jpeg)